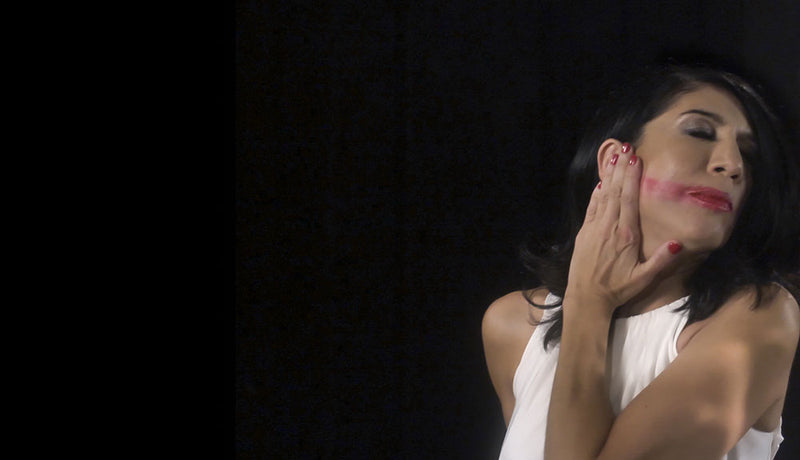

Front Cover: “Dawn of the Cold Season” 2013, C-Print. 24” x 44”

Opposite: “BAAD”, 2013. Digital image.

34

“For me, the most inspiring aspect of this project is the opportunity to introduce the great work and sensibility of an Iranian female icon to the international community. Many Iranian intellectuals consider Forough a cultural godmother of modernist literature in Iran, but she died so young (at the age of 32) that I also think of her as our cultural daughter. A rebel with a cause, Forough spoke with awe-inspiring rawness and maturity. She was an existentialist, feminist provocateur. She was Iran’s Simone de Beauvoir, Frida Kahlo, Maya Deren and Patti Smith all rolled into one. Her work has given me the inspiration to continue my own artistic journey during my 30 years in exile from Iran”. – Sussan Deyhim

ONLY THE VOICE REMAINS:

SUSSAN DEYHIM’S PAN-ARTISTIC HOMAGE By Peter Frank

Artistic lineage does not restrict itself to congruent disciplines. A filmmaker may take inspiration from a painter, a photographer might manifest the work of a novelist, a poet might seek to embody the style and spirit of a choreographer. And with the advent of multi- and inter-disciplinary practices in which disparate art forms overlap or even merge into integrated wholes, artists of all kinds can incorporate the works and methods of those who have come before. If this is not quite collaborating with the dead (collaboration being a consensual act), it is embracing their spirit and paying them the highest homage.

For “Dawn of the Cold Season” Sussan Deyhim has turned to the poetry of a countrywoman and kindred spirit – and, following that spirit, has branched out into territory that she had previously left uncharted. Known for creating a unique sonic and vocal language imbued with a sense of ritual and aura of mystery, Deyhim – who has been performing publicly since the age of 14 – has finally applied her keen sense of dramatic imagery to the production of visual art itself.

Forough Farrokhzad was one of Iran’s leading modernist poets, not only in style (or in lifestyle) but in substance. Active in the 1950s and ‘60s, Farrokhzad helped bring Persian poetry into the twentieth century, not least by living a twentieth-century life herself. By Iranian standards, even those under the westernizing influence of Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, Farrokhzad was a scandalously liberated woman,

someone who insisted on claiming control over her own life, if only to dedicate it to her art. Her art, too, rebelled against the norms of her native society, breaking with fixed traditions of Persian poetry dating back nearly a millennium to follow more fluid standards of form and expression set by European and American imagists and surrealists and existentialists. Charles Baudelaire, Federico Garcia Lorca, and Sylvia Plath were Farrokhzad’s predecessors; but she could sound as much like the Song of Songs (“In that dim and quiet place of seclusion, as I sat next to him all scattered inside, his lips poured lust on my lips and I left behind the sorrows of my heart” – Sin) as she could Ezra Pound (“Remember the flight / The bird is ephemeral” – Only the Voice Remains). Farrokhzad wrote with passion not only

about passion itself, but about aging, death, and the fragile situations in which women remain trapped throughout the world. Deyhim calls her “Iran’s Simone de Beauvoir, Frida Kahlo, Maya Deren and Patti Smith all rolled into one.”

As such, Deyhim recognizes a pre-incarnation in Farrokhzad, a rebel not only “with a cause,” but with much the same cause. Like the poet, the performance artist went to Europe to pursue a deeply felt independent, non-traditional impulse; unlike Farrokhzad (who died in an auto accident in Teheran in 1967, aged 32), Deyhim stayed in the West, moving to New York and more recently Los Angeles. But in America Deyhim has continued to push at boundaries – mostly formal and mediumistic, but also stylistic and contextual. Ironically, by addressing traditional as well as modern themes and exploiting musical and theatrical forms traditional to Persia and neighboring civilizations, Deyhim has mirrored Farrokhzad’s own cultural progressivism: where the elder artist brought the ways of the West to Iran, Deyhim has brought the forms and sensibilities of Middle Asia to the West, morphing them into her work and remaining true to the spirit of her ancient Persian heritage while bringing that heritage into the present with a distinct poetic and dramatic sensibility.

Long aware of Farrokhzad’s writing, Deyhim turned to that verse as a core source for her newest performance work. The poetry proved so forceful that the performance became an embodiment of it – and generated a body of static visual work in order to encompass the breadth of the writing more thoroughly. Seeking to reformulate and amplify Farrokhzad’s sociopolitical message, erotic frisson, and literary eloquence. Deyhim found herself pushed not only to new levels of performative expression

but to the realm of the purely pictorial, a realm into which the musician-dancer- filmmaker-performer had long been tending but had not yet crossed.

Deyhim seized upon several of Farrokhzad’s best known poems to generate sound works, video performances, and photographic images – in fact, carefully chosen video captures – of herself interpreting the poet’s images and feelings. Each of the six series has been drawn from a different poem. For example, Deyhim has manifested Let Us Believe in the Dawn of the Cold Season as a series of self-portraits before a “mirror” (in fact a Mylar scrim) that increasingly distorts the performer’s features. In this manner the reflection betrays a woman’s aging process, to the point where she becomes an object of ridicule and repulsion. Deyhim thus advances Farrokhzad’s lament about the loss of youth and beauty into a critique of present- day ageism. Similarly, the wanton sexual craving and surrender to the desiring gaze that characterize both the ecstasy of Sin and the debasement of Wind-up Doll find the figure of Deyhim wandering city streets, at once in search of love and fleeing from its ravages. In January, Deyhim will premiere another Farrokhzad-based work, the live performance The House is Black, at CAP/UCLA.

As noted, Deyhim has embodied her interpretations in several ways, including the time-based forms of video and live performance but also her new-found medium of photographic prints. There is poetic justice in the fact that Deyhim took to this static format while in residence at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation in Florida. Known best for image- and object-laced two- and three-dimensional objects, Rauschenberg himself was an artistic omnivore, involved in the production of choreography, stage performance, electronic intermix, and even sound. Furthermore, embedded in much

including musicians from Branford Marsalis to Peter Gabriel and visual artists including Lita Albuquerque, Sophie Calle, and Shirin Neshat. It is in her own work, however, that Deyhim has reached the furthest, formally and expressively, and has proven most ambitious in the superposition and even fusion of disparate artistic disciplines. Her work with the poetry of Forough Farrokhzad has brought her to a new level of mediumistic cross-formality. Provoked by the written word of an artistic godmother, Deyhim has elaborated on it with everything from video to sound to staged performance, engaging the human voice, musical instruments, electronic devices and, now, static visual images that extend the spirit and body of Deyhim’s performance onto gallery walls.

October 2014

of his earlier work (coincident with Forough Farrokhzad’s mature writing) are clues to an autobiography laced with pain, struggle, and confusion, much of it having to do with sexuality and social opprobrium. In recognition of Rauschenberg’s spirit, then, hardly less than of Farrokhzad’s, Deyhim expanded the reach of her medial repertoire.

Sussan Deyhim – like (indeed, even more so than) Robert Rauschenberg – is noted for her collaboration with a wide range of renowned international artists,