I moved to New York from Brussels in 1979. After a lengthy and tense interrogation at

the airport, amidst the height of the hostage crisis, I was finally allowed to enter the

metropolis of Manhattan. A dream came through!

I was a dedicated dancer with Maurice Béjart’s Ballet of the 20th Century in Brussels.

But I found myself disillusioned, questioning why I was so devoted to ballet—a 17th-

century European haute bourgeois art form.

I had the incredible opportunity to witness works presented in the 1970s avant-garde

Shiraz Festival of Arts, right in the heart of Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the

Achaemenid Empire. It was a marvel, showcasing a genius mix of international avant-

garde and indigenous roots.

There, I experienced the likes of Karlheinz Stockhausen, the Dagar Brothers, Iannis

Xenakis, The Living Theatre, Peter Brook, Bob Wilson, Martha Graham, Persian

classical music, Indonesian Kecak, Kathakali, and Béjart. These experiences profoundly

shaped my aesthetics and taught me the importance of indigenous cultures and the

forward-thinking vision of avant-garde bridge-makers. Truly inspirational!

When I arrived in New York I was convinced that, despite its fantastic physical bliss and

my love for European classical music, ballet could no longer serve as my philosophical

or artistic sanctuary. With the diverse training I received at Béjart’s school, I decided to

choreograph and compose my own vocal music as the soundtrack.

Stockhausen would often visit our school in Brussels, and one of his disciples, Alain

Louafi, taught us vocal improvisation techniques. An approach that was about blending

elements of indigenous vocal traditions in an abstract, purist electronic context. It

opened an important pathway for what I wanted to explore as a composer and vocalist.

Meeting Richard Horowitz in New York was a turning point. His collaboration with the

great Jon Hassell and being around a circle of composers—each possessing their own

masterful approach to microtonal sensibility, including Pandit Pran Nath, Terry Riley, La

Monte Young, Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and Pauline Oliveros— was transformative.

Richard’s exquisite tonal mastery, his immersion in Moroccan desert trance culture, and

his love for French surrealism—elements he brought back with him after a decade

away—made music my sacred, healing, and cultural guiding light. So, it was goodbye to

ballet, but it will always hold a special place in my heart.

I wasn't an advanced vocalist, but thanks to everything I absorbed from European

choral traditions and the influences around me, I had adventurous ideas about the sonic

and vocal landscapes I wanted to explore. The downtown music scene was a fantastic

playground for creating experimental works; 8-track cassettes and the reel-to-reel tapes

became my lifelines—though bouncing 32 vocal harmonies was a painstaking process!

Then came the challenge in 1983: who in New York City could sing my vocal

compositions? They needed to understand the traditions, have the time, and—who

would play them? Faced with all this, I ended up recording my harmonic ideas myself

and then waiting for commissioning grants to roll in. Let’s just put the ideas on tape.

Thus, the “Me, Myself, and I” approach wasn’t an act of narcissistic self-indulgence but

the only way to ensure my pieces could be composed and heard.

Richard’s musical sensibility and his gift for deep listening profoundly influenced my own

way of hearing. Before I met Richard at Frank Eaton’s studio, Noise NY, in Penn Station,

I had recorded a deconstructed vocal improvisation session that served as the

soundtrack for my new choreographic piece. Frank, who played a crucial role in our

introduction, told me, “There’s someone in town you must meet.” He then remarked, “I

really like the way he holds his head!” At the time, I didn’t quite understand, and I

thought, this cool guy in a studio called Noise NY couldn’t possibly have a class

complex, could he?

Later, during a studio session, as I got to know Richard better, I noticed how he

positioned himself perfectly between the two speakers with an ultra-precise head

posture. That’s when I finally understood what Frank had been talking about—Richard

was a deep listener, all else could wait!

Our duo’s potential attracted cultural luminaries, leading to early performances at

Carnegie Recital Hall, The Kitchen, and the unwavering, instrumental support of Ellen

Stewart at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, who had been invited to the Shiraz

Arts Festival several times, bringing our cultures even closer. We later presented our

work at venues like Royal Festival Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall, BAM, Lincoln Center, The

Met Museum, and The Gnawa Trance Music Festival, where Richard served as artistic

director in its early years, now the Woodstock of Africa.

At the ICA London, Bernardo Bertolucci came to our concert, which led Richard to score

The Sheltering Sky by his mentor Paul Bowles, alongside the great Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Meanwhile, my deconstructed extended vocal techniques raised Lazarus from the dead

in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, scored by Peter Gabriel. Thus

began our journey into film scoring.

With each passing day, it becomes harder to imagine a world without Richard’s witty,

singular sense of humor and his synergistic understanding of all that truly mattered on

both a philosophical and creative level. His humanity and intellectual broadness allowed

him to move effortlessly through any situation, crossing into deep conversations that

became the pulse of the room.

The Wire

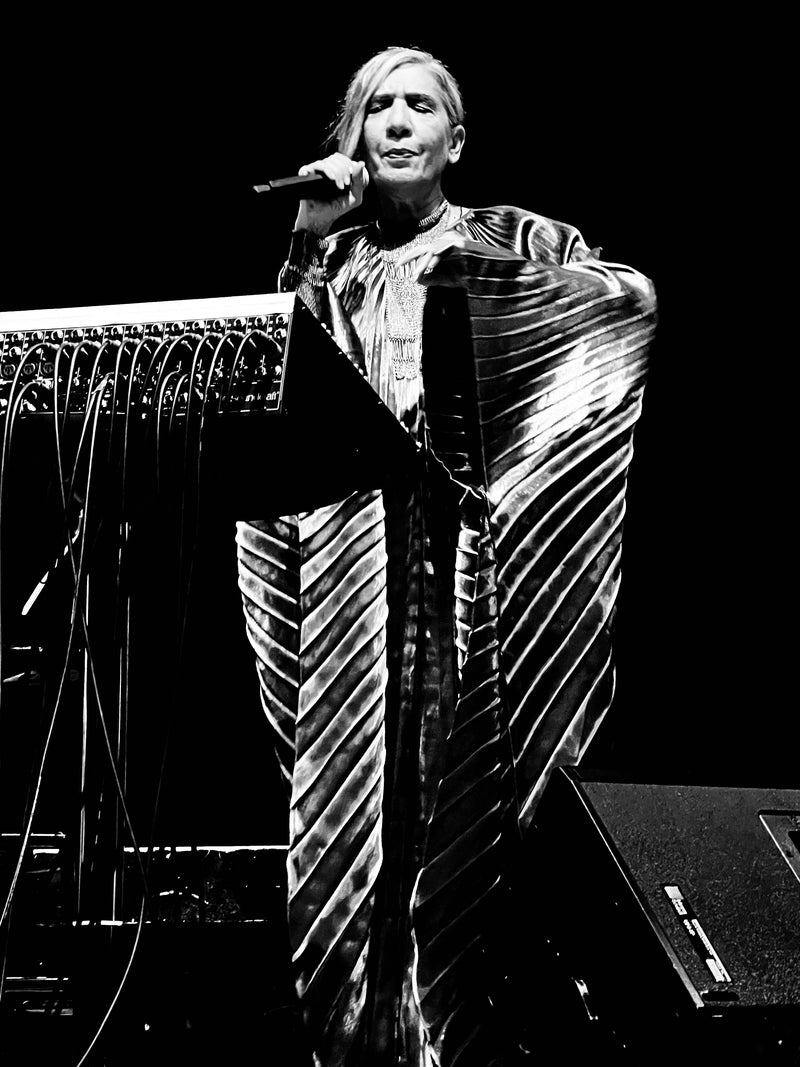

Sussan Deyhim

Epiphanies

This piece will appear in the December 2024 issue of The Wire Magazine.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bnsjo-eAzYg